DALLAS SHERRINGHAM

MOST residents of Pemulwuy, the suburb to the east of Prospect Reservoir, would not realise the history of the area and the remarkable Indigenous man it was named after.

And they would not realise that Pemulwuy, the resistance leader in the Western Sydney area, was the victim of Australia’s oldest murder mystery.

He was a Bidjigal man of the Eora nation born at Botany Bay around 1750 and was to become a brave leader of the Indigenous resistance in the area around Parramatta.

Pemulwuy had a ‘clubbed’ foot which was the result of an Indigenous tradition of inflicting the injury by a club, indicating his status as a ‘clever man’ – a man with supernatural powers,

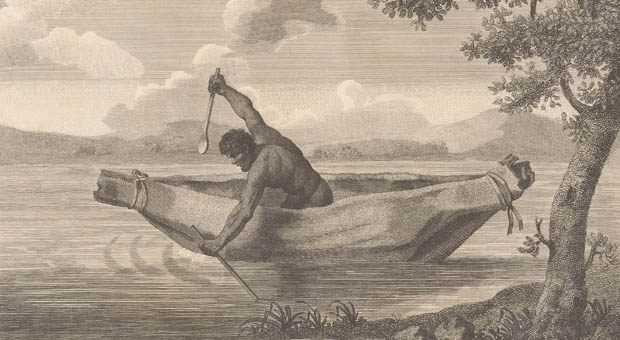

The Eora were the traditional owners of the lands around Sydney Harbor and it had been that way for 30,000 years

They had a complex system of laws that governed social relations, behavior and resource use, a system that the Colonial occupiers had no appreciation of and they regarded the local mobs as ‘savages’.

Parramatta was selected by Colonial Governor Arthur Phillip for its fertile soils and fresh water supplies which he deemed ideal for farmlands and the first Colonial inland settlement.

However, the area was treasured by Indigenous people because it was rich in natural resources including excellent fish stocks drawn to the nutrients of the inflowing freshwater creeks.

Phillip initially maintained cordial contact, having been instructed to treat ‘the Indians’ well and maintain friendly relations.

The settlement of Parramatta was the last straw for Pemulwuy who had provided the struggling Colonial convict town of Sydney with fresh meat.

He was involved in the mortal wounding of John McIntyre in 1790. The unfortunate McIntyre was one of three armed convicts who were sent to hunt ‘game’ to add to the struggling colony’s meagre supplies of food.

McIntyre was feared and hated by the Eora people attack was seen as retribution for his breaking if traditional laws and his violence towards Indigenous people.

Phillip, who had been tolerant , changed his position and sent 50 armed men out twice chasing ‘heads’ of slain locals.

Pemulwuy reacted quickly to Phillip’s hostile about face.

He led a series of raids from 1792, with the first at Prospect and they spread throughout Pemulwuy’s traditional lands in an attempt to halt farming and drive off the intruding Europeans.

They burnt huts, stole crops and attacked travellers. By 1794, the violence between the Indigenous people and the farmers was frequent and extensive.

Pemulwuy’s reputation for bravery grew rapidly and part of that fame was the result of him exposing himself to the armed intruders and being seemingly unaffected by their firepower.

The Battle of Toongabbie led to the British severing the heads of slain warriors to take back to Phillip as evidence.

This in led to the most substantial confrontation in the Sydney area, known as the Battle of Parramatta. Pemulwuy led an army of 100 Indigenous warriors into Parramatta and threatened to spear anyone who tied to stop them.

Soldiers finally opened fire, killing at least five warriors and wounding Pemulwuy in the head and body with buckshot, He survived his wounds and escaped a few days later.

Pemulwuy had become a hero to his people but he was named as an outlaw who could be shot on sight by the newly instated Governor King, who had been Phillip’s compatriot.

In fact, King had ordered that Aboriginals, as they had become known, could be shot on sight near Parramatta, Georges River and Prospect.

Rewards were offered for Pemulwuy dead or alive including a free pardon and fare back to England for any convict or settler who was successful in tracking him down.

The reward proved to be a success. In June 1802, the brave resistance leader was shot dead and his head cut off and preserved in spirits. It was sent to Sir Joseph Banks in England to add to his collection.

No record of the skull

A dispatch from Lord Hobart to Governor King lamented the settlers ‘treatment of Pemulwuy and the Aboriginal population’.

“Be it clearly understood, that on future occasions, any instance of injustice or wanton cruelty towards the natives will be punished with the utmost severity of the law,” his proclamation read.

Just who shot Pemulwuy is a mystery. It was generally believed to be Henry Hacking, but this is disputed to this day. Hacking was a seaman and later explorer who was renowned as ‘a good shot’.

Hacking was a murderer who even attempted to kill his former mistress and ended up being transported to Van Diemen’s Land where he died in 1831.

As researcher Doug Kohlhoff noted: “knowing who fired the fatal shot, does not affect Pemulwuy’s place in history. Pemulwuy was, as King recognised him, ‘a brave and independent character’.”

“He inspired others fought hard and died for his land and his people. For that we can all admire him.’

Pemulwuy’s son Tedbury took up the fight and managed to evade capture until he was killed in 1810. And what about Pemulwuy’s preserved head? Sadly, it disappeared and is still missing.

Prince William announced in 2010 he would return Pemulwuy’s skull to Sydney’s Aboriginal people and Pemulwuy’s relations.

However the Natural History Museum in London had no record of he skull amongst its Aboriginal collection.

Pemulwuy inspired the Redgum recording ‘Water and Stone’ and the novel ‘Pemulwuy: The Rainbow Warrior’. The choral piece “Pemulwuy’ has become a standard performance piece in concerts nationwide,

And the list of Pemulwuy inspired groups and names continues today,. The Sydney Harbor ferry Pemulwuy is just one example.

Sources: National Museum of Australia, Wikipedia